Now it seems that Ilya Averbukh has always been in the professional status in which we all know him now. I remember the story of how many years ago the world-famous American ice impresario Tom Collins agreed on a joint show with the St. Petersburg Figure Skating Federation.

Many Russian figure skaters were invited, including Averbukh and his ice dancing partner Irina Lobacheva. The show went brilliantly, and when it was all over, Ilya very carefully, and not even himself, but through familiar agents, asked if there was any fee for the performance.

The skater was kept in the dark for several hours, then it turned out that the money for the performance was left on the other side of the city in some hotel at the concierge, and when Ilya arrived there at three in the morning and opened the envelope, he saw that there were 500 dollars there.

Even at the time, it was a humiliatingly small amount. And despite the fact that the money was desperately needed, Averbukh left it in an envelope on which he wrote: "Thank you very much. Maybe this amount will help you more than it will help me."

It was then that he said to himself for the first time, "Never mind. You'll come back to us." And, having officially ended his career in 2004, he took up another, not too familiar profession for himself.

On the one hand, Ilya was not the first to try to create a commercial project within the framework of figure skating. In the mid-80s, the Tatyana Tarasova Ice Theater appeared and existed quite successfully for a little over ten years, but it fell apart when the coach returned to the sport. Olympic champions Alexei Urmanov and Artur Dmitriev tried to make their shows in St. Petersburg, but the experience ended badly for both of them - the sale of apartments to pay off creditors. For world champion Maria Butyrskaya, a similar attempt resulted in a debt of $200,<>.

It was both easier and harder for Averbukh. On the one hand, he tried to take into account the mistakes of his predecessors as much as possible and enlist the support of sponsors. On the other hand, even in his professional circle, the ex-figure skater had neither the weight and authority of Tarasova, nor the titles of Urmanov or Dmitriev. In the early 2000s, the "Soviet" ideas about the significance of sports results were still too strong. A silver medal, even at the Olympic Games, meant that you were a loser. That is, no one.

It took several years to start talking to business partners on an equal footing. And then Ilya knocked on the doors, feeling like a beggar, repeatedly received refusals and returned home green from anger and humiliation.

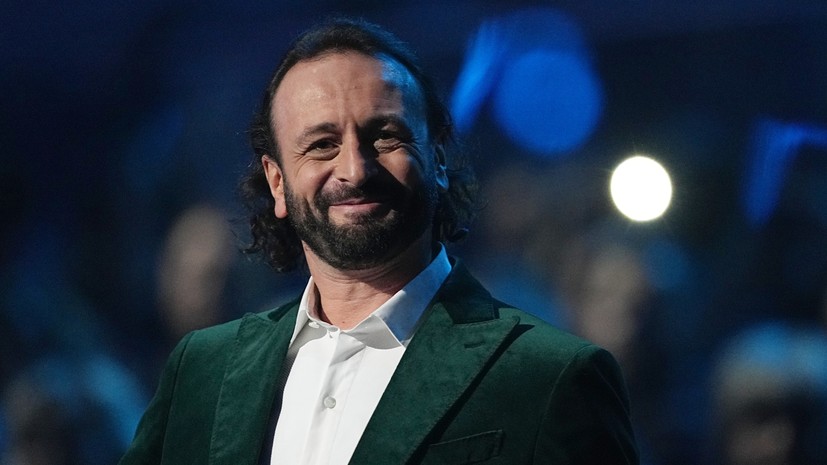

- Ilya Averbukh performs at the anniversary gala concert in honor of his 50th birthday.

- RIA Novosti

- © Alexander Wilf

Now all this is perceived as a story that is good to tell to grandchildren, sitting by the fireplace, but seriously, Averbukh, like no one else, deserves the award, which is presented in many international sports halls of fame for his contribution to the development and promotion of his own sport. Behind this dry and somewhat bureaucratic formulation is the huge, extremely eventful life of many people. Engaged in shows and performances, developing more and more new projects, each of which is different from the previous one.

In fact, even those thousands of children who are brought to the skating rinks by their mothers and grandmothers every year are largely the merit of Ilya's television projects, his ability to convey to people the main, in general, essence of any achievement: nothing is impossible in life. You just have to work. Getting almost the entire show business of the country hooked on the "needle" of figure skating is also a non-trivial achievement, which simply has no analogues in the world.

"Working with Averbukh is a corridor in which new doors are constantly opening for all of us," said Salt Lake City Olympic champion Alexei Yagudin. And, probably, these are not just words, if an athlete rushes to the ice just two months after a complex knee operation and skates on this ice in such a way that it takes his breath away. And, probably, it is no coincidence that it was Ilya, at his anniversary show, that Roman Kostomarov got on skates after a severe tragedy.

Averbukh's relationship with stars, most of whom are much more titled than himself, is a different story. In the most famous and prestigious of the world's shows, Cirque du Soleil has never relied on outstanding performers at all, perfectly understanding the standard thing for any show: if a performance is made with an emphasis on a star, a person immediately has levers to blackmail management, partners, and servants. Here, the picture is exactly the opposite. There have never been so many Olympic champions in any show in the world. Sometimes it even seems that Ilya takes special pleasure in staying in the shadows, while his artists discover more and more new talents in themselves.

"I dream that one day I will sit in a rocking chair in front of the fireplace, wrap myself in a blanket and do nothing. If I suddenly get bored, I'll start swinging," said today's hero of the day, leaving the sport.

Perhaps, indeed, in a decade or two, figure skating will tire Averbukh to such an extent that the producer, burdened with age and worries, will think about a rocking chair. But for some reason, it seems to me that Ilya will put it in the center of the rink. And everything that happens on the ice will continue to revolve around it.

This, in fact, is what I want. Happy Birthday, Maestro!