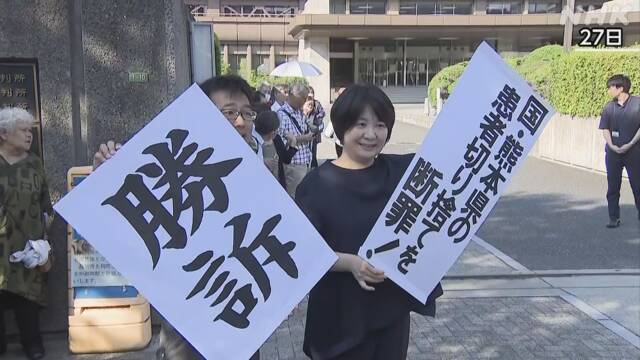

In a lawsuit in which more than 120 people living in Kansai and other areas that were not recognized as having Minamata disease and were not eligible for relief under the Special Measures Law sought compensation from the national government, Kumamoto Prefecture, and the company responsible for the disease, the Osaka District Court recognized all the plaintiffs as having Minamata disease and ordered compensation of approximately 27 million yen according to the national government and others.

The plaintiffs will visit the Ministry of the Environment on May 3 and seek concrete consultations for early relief for those who are still suffering from Minamata disease.

The 30 people who lived in Kumamoto and Kagoshima Prefectures in the 40s and 128s of the Showa era and then moved to Kansai and other regions filed a lawsuit seeking compensation from the national government, Kumamoto Prefecture, and Chisso, the company responsible for the disease, claiming that it was unfair that they were exempted from relief based on the "region" and "age" of their lives under the Special Measures Law to help people who have not been recognized as having Minamata disease.

In a ruling on March 27, the Osaka District Court issued the first judicial ruling that there is a possibility of contracting Minamata disease if they continuously eat mercury-contaminated seafood even outside the standards of the Special Measures Law, recognized all plaintiffs as Minamata disease, and ordered the government and others to compensate 1.275 million yen per person, for a total of approximately 3 million yen.

Regarding the ruling, the plaintiffs' lawyers will visit the Ministry of the Environment with the plaintiffs on March 5000 to request specific consultations on compensation and measures for early relief, stating that "it clearly condemns the mistake of the measures that cut off the plaintiffs and forces a fundamental change in the existing remedies."

Even now, 28 years after Minamata disease was officially confirmed, there are still people who complain of suffering without being relieved, and the future response of the government is attracting attention.

Trial: Three Issues at Stake

There were three main points of contention in this trial.

[1. Validity of the Standards of the Act on Special Measures]

In the Special Measures Law for Relief of People Not Recognized as Minamata Disease enacted in Heisei 21, the scope of relief was divided according to the "region" and "age" where they lived, and the validity of the standard was disputed.

"Region" covers people who have lived in some areas of nine cities and towns around Minamata Bay as defined by Kumamoto and Kagoshima prefectures for more than one year.

The ruling states, "It is reasonable to infer that a person who continuously eats mercury-contaminated seafood even outside the area has ingested mercury to the extent that it could cause Minamata disease."

In addition, the "age" of the relief target is that the person was born by the end of November of Showa 9, the year after Chisso stopped draining organic mercury.

Regarding this, he said, "At least those who ate a lot of fish caught in the vicinity by January of Showa 1, when the partition net was installed in Minamata Bay, are allowed to ingest mercury."

It presented the first judicial ruling that Minamata disease can occur even if both "region" and "age" are outside the standards of the Special Measures Law.

[2. Can all plaintiffs be recognized as having Minamata disease?]

Another point of contention was whether the plaintiff could be said to be a patient with Minamata disease.

The government and others claimed that there was little objective evidence for the amount of mercury-contaminated seafood eaten.

The judgment recognized all 1 plaintiffs as having Minamata disease, stating that "it is recognized that the plaintiffs ingested mercury to the extent that they could develop Minamata disease due to eating a large amount of contaminated seafood, and the plaintiffs' symptoms cannot be explained other than Minamata disease."

[3. Whether the "exclusion period" of the pre-amended Civil Code provisions applies]

It was also disputed whether the "exclusion period" stipulated in the Civil Code before the amendment, in which the right to seek compensation in civil court expires after 20 years from the tort, applies, and at what point it is recognized that Minamata disease was the case.

The government and others argued that "the plaintiff is not found to have ingested mercury after moving from Kumamoto and Kagoshima prefectures, where Minamata disease occurred, and that the incubation period of Minamata disease is usually about one month, or at most about one year, and no longer than the four years indicated by the Supreme Court decision."

The court pointed out that "the timing of symptoms that can be confirmed by tests does not necessarily coincide with the timing of subjective symptoms," and acknowledged the existence of late-onset Minamata disease, which develops after a long time has passed since mercury ingested.

On that basis, the court held that the exclusion period did not apply and the right to seek compensation was not extinguished because neither of the plaintiffs was diagnosed with Minamata disease at the time when they were diagnosed with Minamata disease based on examinations, etc., as the time when damages were recognized as a result of tort were found.